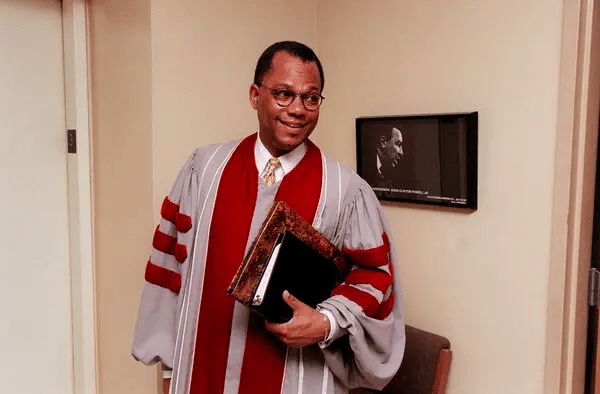

The Rev. Calvin O. Butts III, Dynamic Harlem Pastor, Dies at 73

October 31, 2022

He led Abyssinian Baptist Church and helped revitalize his community by building housing, some of which he reserved for existing residents.

The Rev. Calvin O. Butts III, the Harlem preacher whose talent for oratory and political savvy was a force for social and racial justice, and who raised $1 billion to remake America’s most storied and influential Black neighborhoods, died on Friday at his Harlem home. He was 73.

His son Calvin O. Butts IV said the cause was pancreatic cancer.

In Mr. Butts’s three decades as pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church, his work reflected the dramatic changes in how Americans confronted the nation’s history of racism. In New York, he challenged the white power structure and turned promises into action, creating educational, commercial and homeownership opportunities for Harlem residents.

He took inspiration from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s and by the dawn of the 21st century was a partner of Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg in attempting to create lasting change in Harlem and beyond.

Hired by the church when he was a 22-year-old seminarian, Mr. Butts helped deliver on the soaring sermons of its newly minted pastor, Samuel Proctor, and his immediate predecessor, the irreverent and flamboyant 11-term congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

Transforming his role into a bully pulpit, the urbane Mr. Butts also helped revive Harlem with housing — mitigating gentrification by reserving a portion for existing residents — a supermarket and other commercial development, and a high school.

“Reverend Butts took the idea of building the kingdom of God literally,” Mr. Bloomberg said in a statement after his death.

Mr. Butts also persuaded some record labels and radio stations to reject violent and misogynistic rap lyrics, whitewashed Harlem billboards that advertised liquor and cigarettes, and played politics transactionally to wrest the most resources for his community from whichever party was in power in Washington, Albany and City Hall.

“Reverend Butts worked more effectively than any other leader at the intersection of power, politics and faith in New York,” Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation and former chief operating officer of the Abyssinian Development Corporation, said in an interview. “He understood the role of faith in our lives, especially in the Black community.

“But he also understood power and how to wield it and how to demand power from those who often sought to hoard it. And so he was a pragmatist, he was a realist, but he was also a dreamer.”

The nonprofit Abyssinian Development Corporation became a model for other faith-based development companies that invested in their communities, both in New York City and nationally.

Sheena Wright, Mayor Eric Adams’s deputy for strategic initiatives and the corporation’s former president, described Mr. Butts as a civil rights leader whose “impact from creating educational institutions, commercial development, homeownership, affordable housing and providing social services for those in need will be felt for generations.”

The corporation was established in 1989, the same year that Mr. Butts became Abyssinian’s pastor, prompting him to modulate the rhetoric he had been able to exercise more freely as the church’s second in command.

In that earlier period, he accused some Black elected officials of being too accommodating to the white power structure and Mayor Edward I. Koch of outright racism. He even threatened to run against those officials when they sought re-election — but he never did, although he had dreamed since he was in third grade of someday becoming mayor of New York himself.

When more militant Black leaders balked at cooperating with investigators in the racially motivated killing of a Black man chased by a white gang onto a highway in Howard Beach, Queens, in 1986, Mr. Butts intervened to broker Gov. Mario M. Cuomo’s appointment of a special prosecutor.

But the next year he deftly distanced himself from the accusations of Tawana Brawley, a Black teenager who said that four white men had kidnapped and raped her, a claim that was never proven.

“While we did not always agree, we always came back together,” the Rev. Al Sharpton, who had defended Ms. Brawley, said in a statement.

In 1986, a third of the musicians of the New York Philharmonic, many of them Jewish, boycotted an annual concert at Mr. Butts’s church because he refused to repudiate the Black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan, who had called Judaism a “gutter religion.”

Mr. Butts told The New York Times then that he disagreed with Mr. Farrakhan’s remarks on Judaism, though he supported some of his economic and social positions. But he insisted that he had been asked to flatly denounce Mr. Farrakhan.

“All I’m saying to the Jewish community is, don’t dictate to me,” Mr. Butts said. “I understand your anger. I’m not a fool. I don’t hate Jewish people. In fact, I quite respect what the Jewish people have done. But please don’t make me a boy and tell me what to do.”

During his 33 years as pastor, Mr. Butts weighed his words and chose his battles carefully in reconciling sometimes discordant constituencies: white civic leaders who had anointed him a progressive, responsible Black opinion maker; his own socially conservative congregants; and other Black New Yorkers who were fed up with perceived mistreatment by the police and with economic inequality. He was left jockeying for relevance among them with full-fledged militants like Mr. Sharpton.

Mr. Butts was instrumental in enlisting the Democratic Michigan congressman John Conyers Jr. to convene hearings on police brutality in New York in 1983, hearings that nudged the Koch administration to appoint Benjamin Ward later that year as the city’s first Black police commissioner.

As chairman of the Abyssinian Development Corporation, he funneled some $1 billion into residential and commercial projects in Harlem. Shaun Donovan, the Bloomberg administration’s housing commissioner, said the corporation was “instrumental to the continuing revitalization of the surrounding community.”

Mr. Butts also helped create the Thurgood Marshall Academy for Learning and Social Change, a public intermediate and high school in Harlem.

From 1999 to 2020, he was the president of the State University of New York College of Old Westbury on Long Island. During his tenure, the college gained additional accreditation, established its first graduate programs and expanded its campus.

Mr. Butts was also the president of the Council of Churches of the City of New York from 1998 to 2008; the chairman of the Harlem Y.M.C.A.; the president of Africare NYC, which sought to improve life in rural Africa; and a member of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS.

Calvin Otis Butts III was born on July 19, 1949, in Bridgeport, Conn. His father, Calvin O. Butts II, was a butcher and cook at the Black Angus restaurant in Manhattan. His mother, Eloise (Edwards) Butts, worked as a supervisor for the New York City welfare department.

Calvin learned to read in a one-room schoolhouse in Georgia when he made summer visits to his grandparents there. He was raised until he was 8 in the Lillian Wald Houses, a public-housing project on Houston Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

When the family moved to a private home in Queens, he attended a mostly Black elementary school. But when the Board of Education instituted an open enrollment policy, he was able to take a bus from Corona to Forest Hills and attend the integrated Russell Sage Junior High School.

He graduated from the predominantly white Flushing High School, where he was elected president of the senior class, in 1967.

He was admitted to Trinity College in Hartford, but he couldn’t afford the tuition. Instead he attended the historically Black Morehouse College in Atlanta on a partial scholarship.

He was watching the western movie “Shane” with other students in April 1968 when he learned that Dr. King had been assassinated. He said later that he was one of several people who made Molotov cocktails, burned several stores, firebombed a church and “terrorized cars with whites in them.”

“We were on a good roll,” he recalled in an interview with the research and educational institution the History Makers in 2005. “I looked down at one of these Molotov cocktails, and I looked up at this halftrack truck and this guy with this big shotgun and his very red neck. And all of a sudden I understood that violence was not the way.”

After majoring in philosophy and minoring in religion, he graduated in 1972. He originally planned to pursue a career in industrial psychology or to teach philosophy to undergraduates, but a recruiter lured him to Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan.

He earned a master of divinity degree there in 1975 and a doctor of ministry in church and public policy from Drew University in Madison, N.J. As a pastor, he generally preached against what he considered the sin — abortion included — rather than the sinner.

He was 13 when he first attended Abyssinian; a cousin had taken him to hear Mr. Powell preach. Shortly after Mr. Powell died, a dean suggested that his successor, Dr. Proctor, needed an assistant and noted that Mr. Butts, who was married and had a baby son, needed a job.

In addition to his son Calvin, Mr. Butts is survived by his wife, Patricia Reed Butts, the founder and president emeritus of the Abyssinian Baptist Church Health Ministry; another son, Alexander; a daughter, Patricia Jean Butts; and six grandchildren.

One week after Mr. Butts was hired, he was invited onto the pulpit by Dr. Proctor. That was 1972, he said not long ago, and “I’ve been there ever since.”

He plunged into politics, even circulating nominating petitions for a campaign for school board, but the church’s elders persuaded him against it.

“Why? Because they said, the kinder ones, ‘You’re a young man and we love you. We want to see your ministry grow and develop,’” Mr. Butts said. He then recalled them saying, referring to Mr. Powell, “We’ve already seen one young man destroyed by politics.”

He served as youth minister, assistant minister and executive minister before being named pastor.

While Mr. Butts was much less mercurial than Mr. Powell, he was not to be taken for granted. In 1992, he endorsed the independent candidate Ross Perot for president. In 1995, the same year he invited corporate executives and the Republican mayor and governor to Harlem to raise money for his development corporation, he hosted Fidel Castro at his church.

In 2009, he was said to have promised to endorse the city comptroller, William C. Thompson Jr., for mayor but ended up backing the incumbent, Mr. Bloomberg, after Mr. Bloomberg donated $1 million to the development corporation.

“There is room for the uncompromising, belligerent, nasty, guerrilla activist,” he told The Times in 1995. “But you change when you are responsible for an institution. I got folks I got to pay. I got families.”

“My style was very confrontational, very in-your-face,” Mr. Butts explained in a 2008 interview with Julian Bond, the civil rights leader and former Georgia legislator, for the University of Virginia.

“At once, physical altercation was not impossible for me,” he continued. “My style has, as I’ve matured and grown older and understood more about life and people and traveled, it has become more negotiable.”

Leave a reply